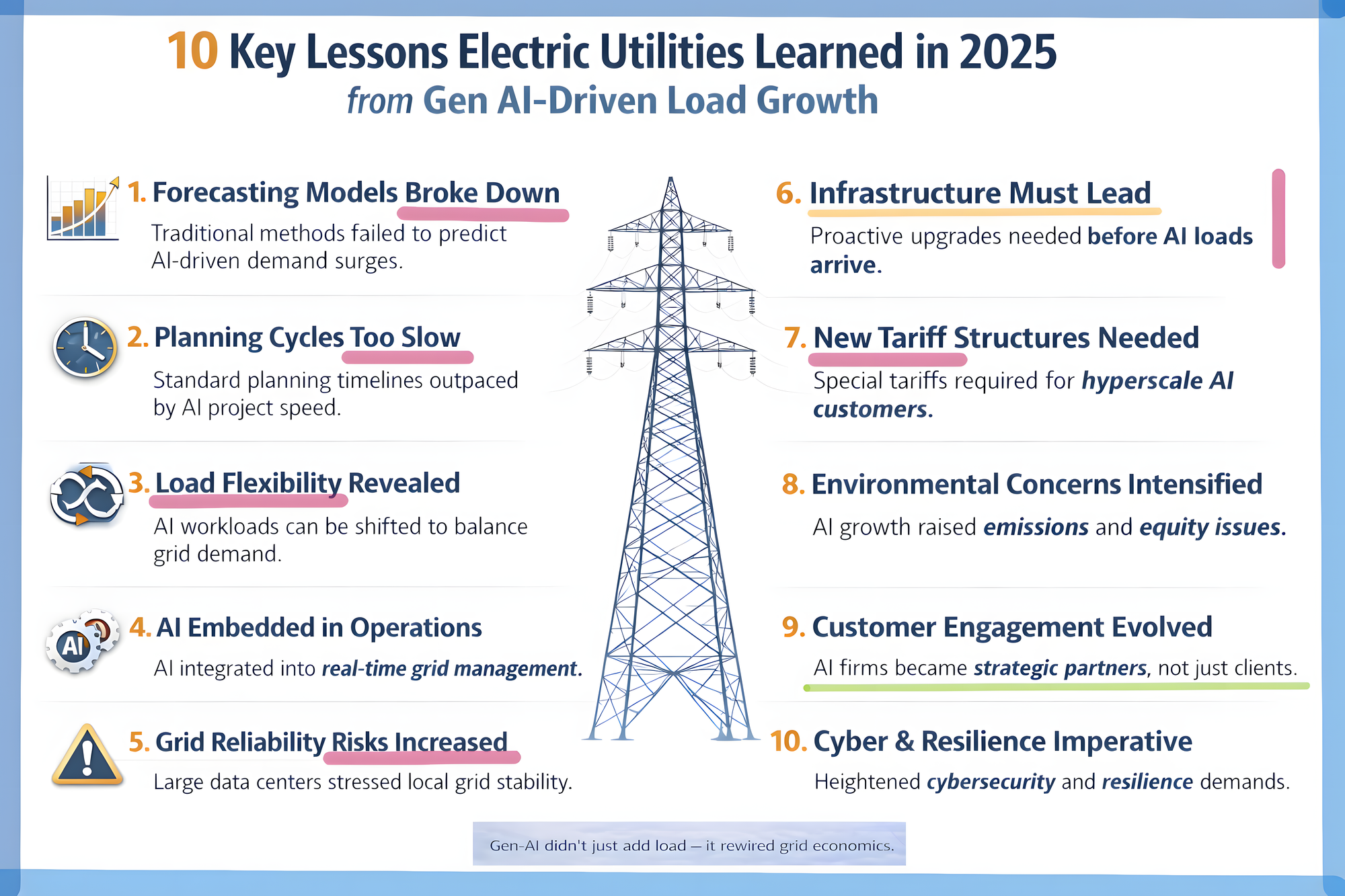

Generative AI didn’t just increase electricity demand—it shattered planning assumptions. In 2025, utilities faced fast, concentrated load, broken forecasts, and new reliability risks, forcing a shift from passive supply to active stewardship of compute-driven infrastructure.

Artificial intelligence did not arrive at the grid as a marginal new end‑use. It arrived as a structural shock—fast, concentrated, capital‑intensive, and deeply entangled with decisions made far outside traditional utility planning. In 2025, utilities across the United States confronted a form of load growth that behaved unlike anything in their historical data. This was not demand creeping in at the edges. It was infrastructure arriving all at once.

What unfolded over the year was not a series of tactical adjustments, but a set of hard lessons about how electricity systems, institutions, and regulatory frameworks respond when computation becomes a primary driver of demand. Taken together, these lessons clarify why generative AI load cannot be treated as a forecast update. It is a reordering force.

- The first lesson was immediate and uncomfortable: forecasting models broke. Traditional demand forecasting is built on gradual adoption curves, stable elasticities, and sectoral proxies that assume continuity. Gen‑AI violated every assumption. Hyperscale data centers moved from site selection to interconnection requests in compressed timeframes. Load appeared in steps, not slopes. Utilities found themselves reacting to public commitments already made by technology firms. The models were not statistically wrong; they were structurally misaligned with a new class of demand that behaves more like infrastructure than consumption.

- Closely related was a second realization: planning cycles were simply too slow. Integrated Resource Plans, transmission studies, and distribution upgrade programs operate on multi‑year cadences optimized for deliberation and stability. AI development operates on quarters. Throughout 2025, utilities repeatedly discovered that by the time a load scenario entered a formal docket, the underlying project had already scaled, relocated, or multiplied. The mismatch was not procedural—it was temporal. Institutions built for incremental change were being overtaken by a sector optimized for speed.

- Not all lessons pointed toward rigidity. One of the more surprising discoveries was that load flexibility was real—and significant. AI workloads, particularly training and non‑latency‑critical inference, proved more shiftable than many traditional industrial loads. With the right incentives and coordination, compute could be paused, relocated, or time‑shifted to relieve grid stress. This reframed AI not only as a source of demand, but as a potential system resource. The constraint was not technical feasibility; it was governance—who controls the shift, under what conditions, and with what accountability.

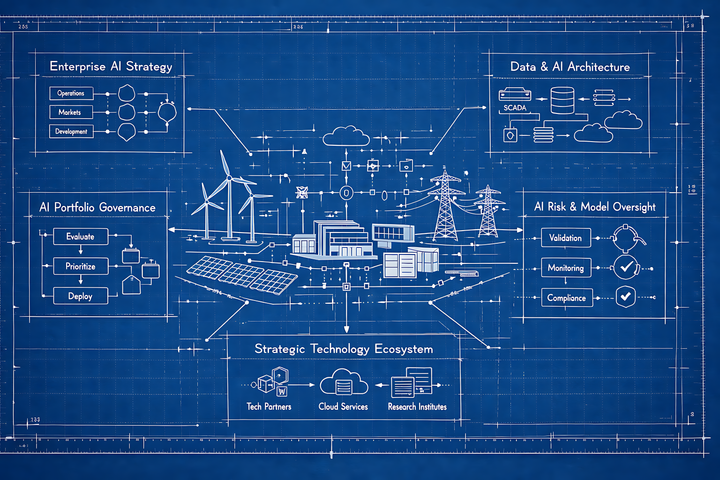

- At the same time, AI was no longer merely something utilities planned around. It became something they used. In 2025, AI embedded itself into grid operations—forecasting, congestion management, outage prediction, asset monitoring. A recursive dynamic emerged: the same technology driving new load was also being deployed to manage the system absorbing that load. Utilities began to experience AI as both pressure and tool, raising new questions about dependence, transparency, and operational trust.

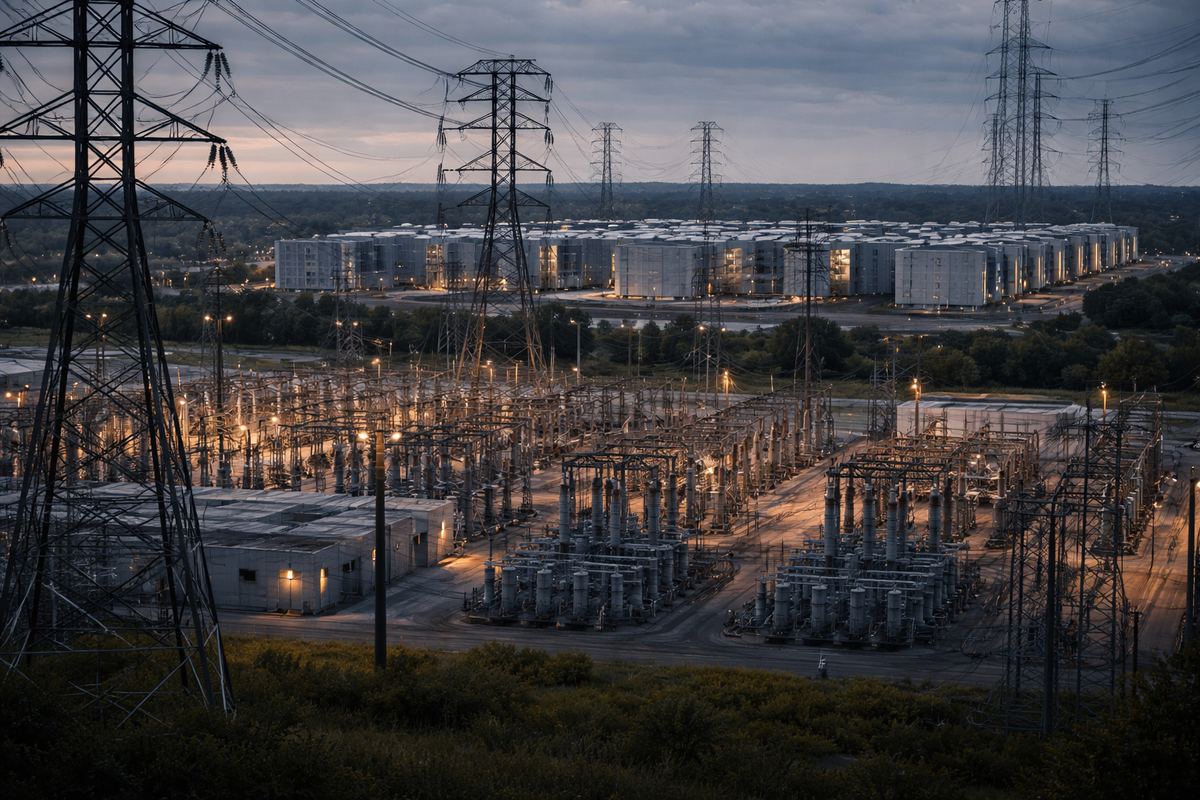

- As AI loads concentrated geographically, reliability risks intensified. Large data centers stressed substations, transmission corridors, and local balancing resources. In several regions, single interconnection requests rivaled the peak demand of entire cities. Reliability planning, historically diffuse and probabilistic, now had to contend with discrete, high‑impact nodes whose failure modes were tightly coupled to digital uptime requirements. The grid was no longer serving many small customers; it was supporting a few extremely large ones—with very low tolerance for interruption.

- This reality reinforced another lesson: infrastructure must lead. Waiting for firm load to materialize before investing proved untenable. By the time AI demand arrived, it was already too late to build transmission, reinforce substations, or site generation. Utilities learned—often painfully—that anticipatory investment, while politically and regulatorily challenging, was the only viable strategy in regions courting AI development. The cost of being early was lower than the cost of being late.

- These pressures exposed shortcomings in rate design. Existing tariffs were not built for customers whose load profiles could double overnight and whose capital decisions were shaped by marginal power prices. Utilities and regulators began confronting the need for new, purpose‑built tariff structures for hyperscale AI customers—structures that balance cost recovery, fairness, and economic development. The old industrial rate classes were too blunt for a customer that was simultaneously system‑critical and system‑flexible.

- Environmental and equity tensions sharpened as well. AI growth raised emissions concerns in regions where incremental supply came from fossil generation. It raised fairness questions where infrastructure investments driven by data centers were socialized across broader rate bases. Utilities were forced to confront a fundamental uncertainty: would AI load accelerate decarbonization by pulling forward clean, firm investment—or slow it by crowding out limited resources? The answer varied by region. The tension was universal.

- The nature of customer engagement changed. AI firms did not behave like traditional large customers. They arrived with their own models, timelines, and strategic priorities—and often expected utilities to act as partners in siting, infrastructure planning, and long‑term power strategy. Managing AI load required executive‑level engagement, cross‑sector coordination, and a willingness to operate outside standard playbooks.

- Finally, cyber and resilience considerations moved from background concern to central imperative. As operational AI proliferated and digital load became more critical, the grid’s attack surface expanded. Reliability was no longer only about weather and equipment failure; it was about software integrity, data governance, and coordinated response across cyber‑physical systems. Resilience planning had to assume intelligent adversaries alongside extreme events.

By the end of 2025, one conclusion was unavoidable. Generative AI did not simply add megawatts. It altered the economics, governance, and tempo of the electric system itself. Utilities that absorbed these lessons began to reframe their role—not as passive providers of power, but as active stewards of an infrastructure now inseparable from computation.