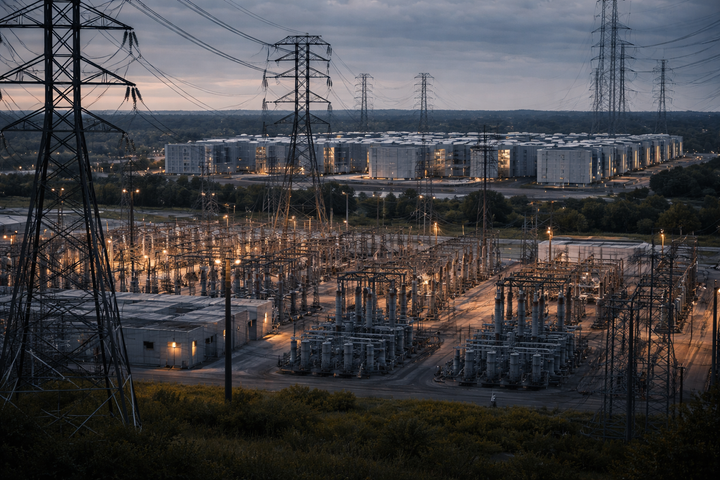

What’s Holding Utilities Back from Scaling the Grid for AI?

AI demand moves in months while grid infrastructure moves in years, creating a strategic mismatch. Unless utilities evolve from building capacity to orchestrating flexible demand, the grid becomes the bottleneck of the AI economy

The energy transition was never meant to unfold at the speed of software. Yet that is precisely the tempo AI has imposed on the grid. Over the past decade, utilities have operated inside a familiar cadence—plan, permit, procure, build—each stage measured in years. AI has no patience for these intervals. A hyperscale data center can surface on a development roadmap in January and demand gigawatts of power by the following summer. EV fast-charging networks scale in quarters, not decades. Industrial automation arrives as a full-stack digital retrofit—instantaneous in operational impact, relentless in its energy appetite.

The contrast is stark: AI-driven demand materializes on the order of months, while grid infrastructure evolves on the order of years. It is a temporal mismatch, but more importantly, it is a strategic one. If left unresolved, the grid becomes the bottleneck to the AI economy—a constraint that shapes where compute clusters form, where innovation concentrates, and ultimately, where economic value migrates.

Utilities sense the inflection point, even if the legacy structures around them were never designed for it. And so the central question emerges: What is truly holding utilities back from scaling the grid for AI? The answer is not singular. It is systemic—woven through regulation, engineering, supply chains, workforce capabilities, and financial architecture. But beneath those structural barriers lies a deeper shift: the grid must evolve from a system built solely to deliver supply into a system designed to orchestrate demand.

The Temporal Dilemma: When Data Outpaces Steel

The challenge begins with timing. AI loads behave unlike any other demand category utilities have ever faced. Industrial parks once took a decade to reach peak load. Residential growth followed demographic trends. Even earlier waves of digital infrastructure—co-location facilities, telecom nodes, server farms—scaled gradually.

But hyperscale AI centers do not scale gradually. They appear fully formed, with procurement cycles measured in fiscal quarters and power needs that rival medium-sized municipalities. Utilities, by contrast, must navigate a planning environment defined by multi-year transmission studies, environmental reviews, permitting processes, and construction lead times. In many regions, a transmission project that begins today will not energize until the early 2030s.

This asynchrony forces a strategic reckoning: utilities built for predictability must now operate in a world defined by immediacy. And immediacy is unforgiving. When demand surges ahead of infrastructure, reliability risk grows. Economic opportunity migrates. Stakeholders—from regulators to OEMs to data center developers—begin searching for alternative jurisdictions that can match the tempo of innovation.

Utilities are not resistant to change. They are constrained by the architecture within which they operate. And five constraints, in particular, define the boundary conditions of their response.

1. Regulation and Permitting: Governance at a Different Speed

Regulation is not a barrier by design; it is a safeguard. It protects communities, ensures transparency, and preserves environmental integrity. But the regulatory framework governing transmission was not built for a world in which gigawatts of new load can materialize with almost no warning.

Every mile of transmission becomes a negotiation across dozens of stakeholders. Environmental impact assessments unfold in sequential reviews. Right-of-way discussions cascade across local jurisdictions. Interconnection studies, already burdened by renewable queues, become chokepoints that delay projects measured in months of engineering work but years of administrative throughput.

The result is a predictable pattern: utilities can see the load coming, but cannot break ground before the load arrives.

Some regions are beginning to experiment with fast-track zones—pre-assessed corridors designed to compress approval timelines. Others are developing more robust, data-driven regulatory cases that quantify reliability risk, economic opportunity, and the cost of inaction. Still others are reshaping their General Rate Case and Risk Assessment filings to anticipate the shifting geography of AI demand.

These efforts point toward a new regulatory rhythm—one that maintains rigor but recognizes that delay itself has become a systemic risk.

2. Physical Capacity: When Conductors Become the Constraint

If regulation governs the pace, physics governs the limits. Much of the U.S. transmission system is already operating close to thermal and voltage thresholds. The grid was not overbuilt; it was right-sized for an era of steady, incremental load growth. AI breaks that equilibrium.

Paradoxically, the challenge is not always generation. In many regions, ample power exists. The constraint is the ability to move that power—across constrained corridors, through aging substations, into rapidly growing load pockets that lack the infrastructure to serve them.

Utilities have begun turning to real-time intelligence to stretch existing assets. Dynamic Line Ratings—a technology mandated in spirit by FERC Order 881—offer a revealing insight: capacity is not a fixed number but a dynamic condition influenced by weather, conductor temperature, and loading patterns. With real-time monitoring, many lines can carry 10–30% more power safely, without new steel or new permits.

Advanced conductors, topology optimization, and probabilistic planning further expand what existing networks can handle. Yet the principle remains the same: physical infrastructure is slow, digital augmentation is fast—utilities must leverage both.

3. Supply Chains: Scarcity as a Structural Reality

Even when engineering designs are complete and permits approved, utilities face a challenge that rarely makes headlines but determines the fate of nearly every project: the supply chain.

Large power transformers now carry lead times of 18–36 months. Protection and control systems routinely take more than a year. Switchgear, relays, and voltage control systems—once predictable procurement items—are now global bottlenecks.

The irony is striking: the grid is held back not only by regulatory process or physical constraints, but by the availability of steel, copper, and silicon.

Some utilities have responded by standardizing equipment designs to reduce procurement fragmentation. Others have negotiated long-term manufacturing capacity reservations, much like hyperscalers reserving cloud capacity. A growing number are pursuing co-investment models in which data center developers help finance procurement commitments in exchange for accelerated timelines.

The lesson is clear: grid readiness is not only an engineering challenge—it is a supply chain strategy problem.

4. Workforce and Skills: A Grid Built for Determinism Entering an Era of Probabilistic Operations

The modern grid is becoming a digital organism. Its signals come not only from SCADA but from millions of AMI meters, phasor measurement units, DERMS platforms, and IoT devices. Managing this organism requires fluency in machine learning, probabilistic modeling, cybersecurity, digital twins, and real-time automation.

Utilities possess deep expertise in deterministic operations—rotating machines, fault currents, protection coordination, contingency planning. But the AI-era grid behaves differently. It demands an operational model that blends engineering intuition with algorithmic intelligence.

The workforce challenge is not a skills gap alone; it is a paradigm gap. Utilities must expand their technical repertoire while preserving the reliability ethos that defines their culture.

Training programs in AI, advanced analytics, and OT/IT integration are beginning to take shape. Partnerships with engineering firms and hyperscalers are becoming strategic rather than transactional. Joint innovation centers are emerging as accelerators where grid operators learn directly from technology OEMs and vice versa.

This is not a transition from mechanical to digital—it is a convergence. And convergence demands a workforce fluent in both.

5. Funding and Regulatory Approval: When Digital Value Meets Analog Frameworks

The final constraint is conceptual rather than technical. Regulators understand the value of physical assets—substations, transformers, wires. Their benefits can be quantified, depreciated, and recovered within familiar frameworks.

Digital infrastructure is different. Its benefits are systemic, distributed, and often probabilistic. An AI analytics platform can improve reliability, but it does so indirectly—by predicting failures, shaping load, preventing overload conditions. A DERMS platform can mitigate wildfire risk, but the value is expressed as avoided events, not constructed assets.

And so utilities encounter a paradox: the tools needed to manage AI-era load growth are digital, but the regulatory mechanisms that approve investments in those tools remain analog.

Some utilities have begun framing digital investments explicitly in terms that regulators recognize—SAIDI/SAIFI improvements, wildfire mitigation outcomes, and reliability risk reduction. Others are leveraging federal funding to reduce ratepayer exposure. Still others are experimenting with shared investment models in which hyperscalers co-finance digital modernization as part of interconnection agreements.

The shift is gradual but inevitable. As the grid becomes a digitally orchestrated system, the regulatory models governing it must evolve.

A Deeper Transformation: From Building Capacity to Orchestrating Flexibility

Solving these five constraints accelerates infrastructure deployment—but acceleration alone cannot close the temporal gap between AI load growth and grid expansion. The deeper shift is conceptual. For more than a century, utilities have operated under a single assumption: demand is firm and must be served with firm supply.

AI upends that assumption.

Modern data centers are not rigid consumers of electricity. They possess on-site backup generation, battery storage, advanced load management systems, and the ability to shift non-time-sensitive compute tasks. They are flexible—even if today’s regulatory structures do not treat them as such.

A study from Duke University crystallizes the opportunity. If data centers curtailed load for just 22 hours per year—0.25% of the time—the grid could accommodate an additional 76 GW of demand without adding a single power plant or transmission line. The implication is profound: the fastest path to scaling the grid for AI is not only building more capacity, but unlocking flexibility in the demand that uses it.

This is not theoretical. Flexible interconnection agreements are beginning to emerge, offering non-firm service that connects faster with lower cost. Dynamic tariff structures are aligning economic incentives with periods of grid stress. And utilities are increasingly exploring how behind-the-meter assets—backup generators, battery systems, thermal storage—can participate directly in grid operations.

In this future, demand becomes an orchestrated asset. Data centers shift load in response to grid conditions. AI workloads dynamically migrate across regions based on real-time capacity signals. The grid stops treating load as an immutable requirement and instead treats it as a resource—a tool that can be shaped, modulated, and dispatched.

This is the paradigm shift: from infrastructure as destiny to flexibility as strategy.

The Path Forward: Utilities at the Center of the AI Economy

The utilities that lead in the AI era will not follow a single strategy. They will follow a dual one. They will accelerate traditional infrastructure—permitting reform, dynamic line ratings, standardized procurement, workforce evolution, and modernized funding. But they will pair that acceleration with something far more transformative: a commitment to load orchestration as a core operational capability.

The grid becomes not merely a delivery mechanism, but a platform. A system where physical capacity and digital intelligence reinforce one another. A system where flexibility carries as much strategic value as steel. A system where utilities shape demand rather than chase it.

AI does not wait for infrastructure. It expands along the fastest available pathway. The regions that modernize their grid operations will become gravitational centers for AI investment, economic growth, and technological leadership. Those who do not will find themselves constrained not by engineering limitations but by the assumptions they failed to abandon.

The future of the grid will not be defined solely by the assets utilities build. It will be defined by the intelligence they deploy, the flexibility they unlock, and the pace at which they adapt to a world where demand moves faster than steel can be set.

Utilities now stand at a crossroads—one defined not by risk, but by opportunity. The AI economy is forming its infrastructure map today. The question is simple: who will build the grid it needs, and who will watch opportunity flow to those who do?